DATELINE KARGIL PART V

DATELINE KARGIL PART V

Munshi Aziz Bhat Museum, A Walk Into The Past

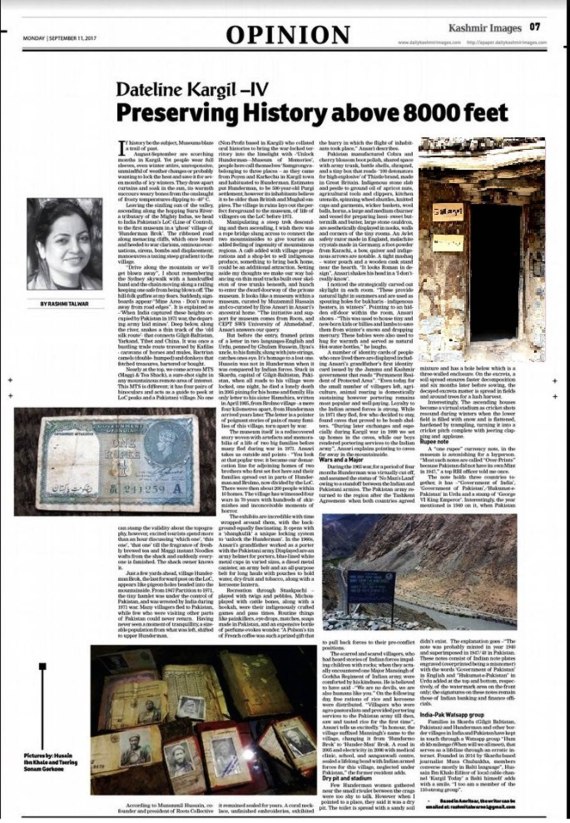

Rashmi Talwar

The sun became milder taking on a tangerine halo. As we returned to Kargil, I was to learn a Hill-folk jugaad- Reversing the vehicle deep into a waterfall on the road, gave a fabulous car-wash! The trade through silk route was etched along waterways and rivers; Munshi Aziz Bhat was one such towering Silk Route trader, a pioneer, visionary, social entrepreneur and above all a collector.

Sarai- a treasure trove

Along the gushing Suru River, Munshi Aziz Bhat built a Caravan Sarai in 1920 and a wooden bridge over the raging river. The three storied Sarai besides serving as an Inn for travellers and traders from Kashmir, Tibet, China, India and Central Asia, had seven shops set up by Bhat. The ground floor used as stable for rest and feed to transport animals and a comfort zone for exchange of goods, cultures and news. Rich and precious wares along with commodities were bartered or bargained. A treasure trove of these collections was accidently discovered by Bhat’s grandson Ajaz Hussain Munshi. “We were about to raze the old Sarai building but ended up curating its treasures into –‘Munshi Aziz Bhat Museum of Central Asian and Kargil Trade Artefacts’.

The story went like this – “A mason chanced upon a sizeable turquoise in the Sarai building and informed us. My father, who was ill at the time, told us about many such possessions and goods lying in the basement of the Sarai. Around this time a researcher Jacqueline Fewkes came looking for us, she had letters in her possession from my grandfather. That was a turning and starting point of the museum set up in 2004,” Ajaz, its curator tells us, and adds “ In 2005 the museum that was then supported by India Foundation for the Arts and Roots Collective, attracted researcher Latika Gupta to Kargil as its curator. The result was a building designed to look like a thriving old market, above our home!”

Walk into History

I walk the trail to the museum, which is just a few steep steps ascending, shadowed by leaves of fruiting ripe apricots and still-green baby grapes. The view from here is spectacular of mountains overlooking the Suru River.

The museum proved an exceptional glimpse into the Indian and Central Asian trader-culture of 19th and early 20th centuries. Collection of artefacts and mercantile, exhibit the enormous range, apart from services, jingling their merry ways, on many maritime and overland trajectories of Silk Route, by traders. Adding on to the story –“The traders were as varied as their buttons ! – Punjabis and Kashmiris, Afghanis and Persians, Chinese and Tibetans, Spaniards and Somalians, Egyptians and Italians rubbed shoulders, broke bread and bartered and bargained for goods with Dardis, Argons, Baltis, Bohto, Purkis, Tajiks and Uzbeks. One can imagine the loads and varieties of goods that arrived here.

Many such items were stored in the Sarai. We found some 4,000 pieces dating back to 1800s, and set up the exhibits along with my brother, Gulzar Hussain Munshi as Director and Muzammil Hussain Munshi as its outreach programmer,” the Curator of the museum fills in.

Interestingly, “Munshi Aziz Bhat, was once the official petition drafter for Maharaja of Kashmir, before he ventured into trade which was mostly then controlled by Punjabi Sikhs and Hoshiarpuri Hindu Lalas. Kargil Khazana, Resham Raasta and the Sarai, encased the narrative of life in Kargil- a melting pot of trades.” Ajaz explained –“Kargil is a nodal point, equidistance from both Leh and Srinagar, in addition to links with Tibet, China, through Gilgit-Baltistan to Afghanistan, gave it an enviable position in Karakoram ranges lower than Himalayas comparatively being an easier passage for traders,” Ajaz pools in, while showing us horse saddles from British times, bridals, drapings, camel trappings, horse foot nails from ‘Mustang & Sons’ and equine accessories of yore. Besides polo sticks and balls, helmets and gloves.

Plant that preserves

I lift up a dry twig, placed in every glass enclosure of artefacts, clothing, paper testaments -everywhere– “what is this?” “It’s dried Khampa twig to prevent critters, moths, beetles, termite, silver fish and every other bug”, and I learn another hill folk nuskha – prescription.

Memorabilia

The mercantile turned memorabilia is an enduring peek into lives of merchants, horsemen, herders, pilgrims, artisans, nomads, travellers and farmers that despatched and received essentials and the luxurious. Besides this, the path saw many a wayfarer, besides potters, weavers, jewellers, blacksmiths, cooks, porters, even pimps, prostitutes and Princes. “The overland and sea silk routes were famous during the reign of Alexander the Great and Han Dynasty in China and became a transcontinental thoroughfare for goods transported using horses, mules and donkeys, to camels and yaks, besides on foot”, feeds in the curator.

I am completely astonished by packets of chemical dyes of Batakh brand from my hometown Amritsar, from late 19th century, the brand carried through 60s and 70s too.

Munshi holds one of the three jade pieces –“This is a ‘Zehr Mohra’ cup that detects any poison by changing colour of the brew.” Then removing his ring, he pulled a whole yarn of Dhaka Malmal’- one of the most prized fabrics produced in Bangladesh, and made it pass smoothly through the ring.

A gramophone of 1905 by Columbia, a lantern dating to year of Indo-China war of 1962, German petromax lantern, huge stone cauldrons and giant ladles used during festivities, samovars and bukharis from Bukhara, a pair of colourful socks from Yarkand, opium snuff-boxes from all over and their dainty cases are all here.

“We even have documentary proof that the King of Hapur in Skardu owes 6,000 in silver currency to my grandfather,” Ajaz laughs showing us a rare Russian 100 rouble that made its way to Kargil measuring 48 sq inch rectangle.

The artefacts range is extensive, Nanakshahi coins and currencies of the world, jewellery, carpets, hosiery, utensils, clothing, armoury to paintings and manuscripts. Assorted caps – Kashmiri, Karakul, Tajik, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Mangolian, Turkish, Balti and Glass Shades from Yugoslavia, Germany and England too are displayed in the Museum.

Trends and Happiness quotient

Many types of merchandise set up trends for the elite. If one was to serve Hookah, Yarkand ones were considered the best. If rugs were to be bought they had to be the Kashgar ones, thus silks from Khotan, buttons and combs from Italy, “every item hides a story of its travels” the museum director Gulzar Hussain Munshi believes. Similar were the inclinations for food- as in salt from Akshai Chin, spices from Hind, Rice from Kashmir. It was thus fashionable to serve Tea from Tibet and Apricots from Skardu.

Kargil’s large heartedness is evident in their hospitality, in not over-charging tourists and visitors, their Happiness quotient thus, is high, which manifests itself in the fact that many additions to the museum were free contributions from the local populace, for instance, a recent gift of hand-written Koran along with precious Tibetan manuscripts claimed by owner to be about 600 years old. Ravinder Nath and his wife Madhubala the lone Hindu family of Kargil gifted the family’s prized possession – a “Passport” issued to Ravinder’s grandfather Amar Chand – which reads – Lala Amarchand resident of Jahan Kalan, Hoshiarpur, issued by the order of ‘Her Majesty Counsel General at Kashgar’- British Subject by Law”. It may be one of the rarest of passports. Once the museum attracted attention, the tourism department too promoted it and along with that came the trust. Thus, locals who were suspicious of antique proxies started contributing voluntarily. “No one has ever asked me for money,” Ajaz beams with pride.

Photographic memory

The photographic display of Italian geographer and explorer Giotto Dainelli taken in 1904, of rows of caravans of camels, mules and horses – carrying traders along this historic route, did set the stage for documenting the precious history of the bubbling cauldron of trade. This is amply supplemented by Rupert Wilmot’s collection -‘The lost world of Ladakh Early Photographic journey 1931-34,’ as a feast, to draw and delight generations.

On Heritage track

The incredible wheel of trade may have been clogged by war-boundaries, but the trodden paths have left in their tracks, a treasure chest of exquisite heritage that Kargil sits on, waiting to be explored and showcased for the world.

The scorching heat melts, dipping into light cirrus clouds, the smouldering light of the morn, curls and spirals into a dramatic sky theatre before curtains call. Unquestionably, tomorrow is just a wink away when silk rays will again draft a new Horizon; every snowflake will reveal its story. To inquisitive tourists, descending upon this region to peek into Kargil’s glorious past of Emperors, Kings and Queens, of palaces and forts, sculptors and faiths, savouring its surreal tales and exquisite beauty.

Rashmi Talwar, is an Amritsar based Independent Writer, can be emailed at: rashmitalwarno1@gmail.com

URL:http://dailykashmirimages.com/Details/149180/munshi-aziz-bhat-museum-a-walk-into-the-past?

Photos : KT Hosain Ibn Khalo

Dateline Kargil –IV

Dateline Kargil –IV Dateline Kargil III

Dateline Kargil III

Recent Comments